Eva Atlan is our Head of Collections. For years, she had been researching the work and life of Frankfurt artist Rosy Lilienfeld, now largely forgotten. Here, she offers an overview of her findings so far.

Sacha Schwabacher, 1935, in: Israelitisches Gemeindeblatt, No. 9, May 1935Rosy Lilienfeld lived in a particular world. In reality, she lived almost entirely in one place, in Frankfurt, the city where she was born, but in her unreal life in art, she lived in the north and south, in heaven and hell, in the infinite.

This is how the art historian Sacha Schwabacher described the artist Rosy Lilienfeld in 1935, an expressionist who is largely unknown today. Her life and work need to be rediscovered, because only a few biographical data are known about her.

Who was Rosy Lilienfeld, and what became of her?

Rosy Lilienfeld was born in Frankfurt am Main on 17 January 1896. Her father was Ludwig Lilienfeld (died 1935); her mother Esther, from Melbourne, Australia, was known as Minnie. The family lived in Frankfurt’s Westend district. On 17 July 1939, Rosy Lilienfeld's mother applied for permission for herself and her daughter to emigrate to England. She also gave notice on their apartment in Arndstrasse as of 1 October 1939. But rather than their journey taking them to England, it took them to Holland. From 23 November 1939, Rosy Lilienfeld was registered as resident in Rotterdam. She lived at a variety of addresses in the city until 25 February 1941. At that point, all traces of her mother are lost; her name is also not on the deportation lists. On 26 February 1941, Rosy Lilienfeld moved to Utrecht. There, she was arrested the following year and moved to the Westerbork transit camp. She was then deported to Auschwitz, where just a few weeks later she was murdered.

The artist Rosy Lilienfeld and her rich oeuvre

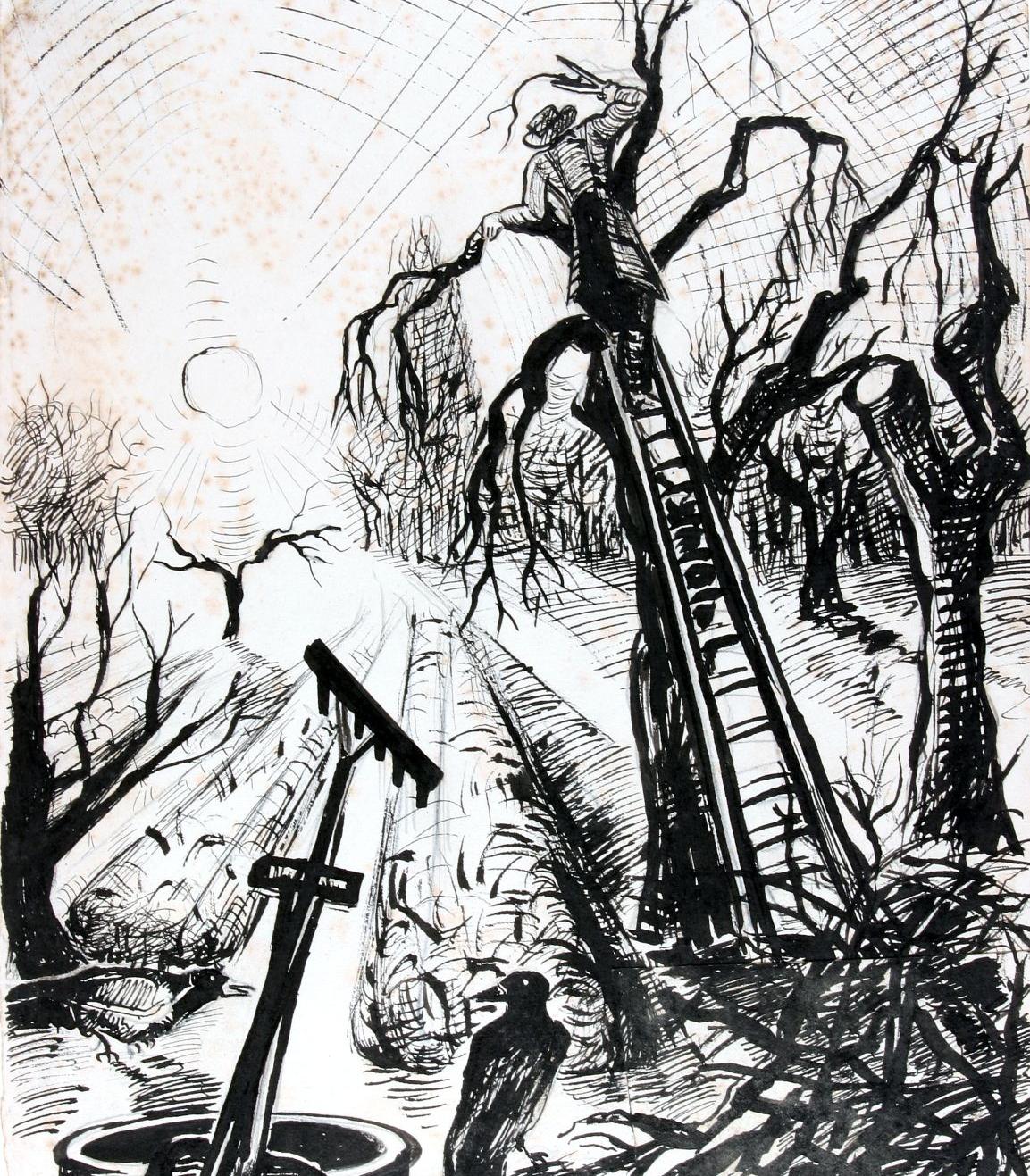

Our collection contains around ninety ink and charcoal drawings by Rosy Lilienfeld as well as a number of prints. The museum acquired approximately half these works from the art trade in the 1990s. Largely from the mid-1920s, these are primarily expressionist landscapes and Frankfurt cityscapes. Some of Lilienfeld’s compositions are imbued with a strong sense of unease. Their almost nightmarish atmosphere may be an indication of the artist’s mental state. As records show, after first attempting suicide in 1923 she was diagnosed as manic depressive and was in regular psychiatric treatment until 1935.

I first came across these works in 2009 while reviewing our entire collection of prints and drawings. Immediately taken by Lilienfeld’s powerful artistic expression, I then began to research the life and work of this almost forgotten artist. Although she mainly worked as an illustrator, only one book with her illustrations was ever published – Bilder zu der Legende des Baalschem / Pictures to The Legend of Baalschem (1935). Two articles published in Frankfurt’s Israelitisches Gemeindeblatt in 1935 and 1937 offer an insight into Lilienfeld’s artistic work and early exhibitions. These articles, both by art historians, provided helpful information. Research at the Hesse Main State Archives in Wiesbaden and into the Frankfurt Devisenstelle (Foreign Currency Transaction Office) files also proved very fruitful. Applications for exit visas had to be accompanied by a detailed inventory of all household goods, and not only was the Lilienfeld inventory included in the files, but so were Rosy Lilienfeld’s extensive medical records. These initial research findings were then publicly presented in a showcase exhibition opened in 2009 (Frankfurter Stadtansichten, 8 Sept. 2009 – 21 March 2010) – almost certainly the first official show of this artist’s works since she fled Germany in 1939.

Between 2012 and 2019, the Jewish Museum Frankfurt was able to acquire nearly another forty works by Rosy Lilienfeld. Including illustrations of works by Edgar Allan Poe and Joseph Roth as well as Hassidic stories and messianic subjects, these reveal the diversity of topics and range of expressive styles of this almost forgotten artist. Hence, in the course of this research, despite the paucity of biographical details and information about Rosy Lilienfeld, it has been possible to ‘consult’ a large number of her diverse works from the early 1920s to the mid-1930s.

Lilienfeld’s studio in Sachsenhausen

In the early 1920s, Rosy Lilienfeld studied at the Städelschule art academy under artist Ugi Battenberg. The Städelschule also provided her with a studio in the Sachsenhausen artist’s quarter until 1936, when the contract was terminated. Unemployed from 1933, Lilienfeld could no longer pay the rent for the studio. In 2019, when some of Lilienfeld’s etchings came onto the art market together with a previously unknown photo of her studio, we immediately took the chance to acquire them. The photograph, probably from the early 1920s, shows her studio with various portrait paintings as well as landscapes and a café scene, all in oils. With none of Lilienfeld’s oil paintings known to have survived, this photo is now a unique witness to this part of her oeuvre.

The photograph of the studio was not the only exciting discovery. The etchings included several portraits, and we have successfully identified two of the sitters. One of the etchings is a portrait of Ugi Battenberg (1879-1957).

Together with his wife Fridel (a pianist) and his sister Mathilde (a painter), Battenberg belonged to those artists playing a significant role in Frankfurt’s vibrant arts scene in the 1920s. Against the conventions of that time, Battenberg studied with a woman artist – Ottilie W. Röderstein (1879-1937). Later, he integrated late impressionist ideas into his art, a style decisively influencing a number of artists including Max Beckmann. As mentioned in the Israelitisches Gemeindeblatt article cited above, Battenberg was not only important in Lilienfeld’s studies, but also instrumental in organising the first exhibition of her works.

Sacha Schwabacher, 1935, in: Israelitisches Gemeindeblatt, No. 9, May 1935Rosy Lilienfeld’s career rapidly took off. Evidently a caring mentor, Battenberg arranged for the young artist, apparently less practically minded, to hold her first exhibition in the art association’s central room. (Later her works were also exhibited in the Städel’s department of prints and drawings.)

The other portrait where the sitter has been identified is signed and dated 1923. Most probably, this etching, with the monogram ‘OR’ at the top left, shows the painter Ottilie W. Röderstein (1859-1937). At this time, Röderstein was a well-known artist who was also very active in social issues. By supporting and promoting young women artists, Röderstein sought to improve the visibility of women in art. So it is certainly significant that she sat for Lilienfeld’s portrait, and may well be an indication of the latter’s network in the Frankfurt art scene. Since Röderstein had been Ugi Battenberg’s teacher, he may have initiated the contact to Lilienfeld hoping to give this young woman artist a chance to show her works in other exhibitions.

Frankfurt city views

Lilienfeld’s city views from 1926 to 1929 were strongly influenced by Max Beckmann’s works. Teaching at Frankfurt's Städelschule art academy since 1925, Beckmann was a good friend of the artist Ugi Battenberg. In her sketches, Lilienfeld often revisited the view of the inner city from the River Main’s southern bank, took the Eiserner Steg footbridge as her subject, or depicted scenes of the industrial Ostend district and the vista across the railway bridges to the Osthafen harbour. The Sachsenhausen artists’ district, as it was known, was home to her studio and the area also provided a variety of subjects. The wealth of her drawings from this period is impressive. Many are not just sketches, but works in their own right, offering an insight into Lilienfeld’s own milieu.

Rosy Lilienfeld’s many city views testify to her prolific output as an artist –a productivity found similarly, if not even more intensively, in her illustrations of literary works and Hassidic sources.

Literary inspirations

Our collection contains one illustration from 1931 to Gottfried Keller’s Tanzlegendchen (Legend of the Dance). The sketch shows King David surrounded by angels, with the dancer Musa kneeling at his feet. They are set in a heavenly sphere, removed from the world. In a different realm on the lower edge of the scene, a man is standing at the centre of a group of figures. Some of the women and girls are looking up towards the heavens, while others are absorbed in prayer. Here, Lilienfeld depicts the moment in Keller’s story when Musa, the main protagonist, was dancing a prayer to the Mother of God and, suddenly, King David appeared to her. He promised Musa would dance eternally in heaven – if she renounced dancing for the rest of her days on earth. But why did Rosy Lilienfeld take this literary source as an inspiration for a series of illustrations? Keller’s story of Musa deals with art and artistry, with heavenly joy as a reward for worldly renunciation. In this, it also reveals the author’s own attitude towards art and religion. Without self-denial, Keller seems to say, there can be no art – yet ultimately, heavenly beauty is not a substitute for the beauty of the world.

Illustrations of Joseph Roth’s Hiob

In 1931, Lilienfeld appears to have been fascinated by Joseph Roth’s recently published novel Hiob (translated into English as Job: The Story of a Simple Man). As suggested by the numbering on the three sketches in the museum’s collection, she must have completed at least 41 sketches as illustrations. This almost obsessive exploration of Roth’s story is characteristic of Lilienfeld’s approach since she usually worked in comprehensive series. Set in the twentieth century, Roth’s novel is not solely based on the biblical account of Job, who loses everything, but also creates an analogy with the story of Joseph. As that story recounts, when Joseph tells his brothers of his dream of God’s omnipotence, they misread it and start to plot against him. In both Roth’s novel and the biblical story of Joseph, a brother is either teased or tormented by his siblings. In her illustrations, Lilienfeld adopts a particular style very different from her earlier city views. These are ‘graphic novel’ illustrations which can be linked precisely to the events in the narratives, just as here when Menuchim’s brothers try to drown him in a water butt.

Edgar Allan Poe "Loss of Breath"

In 1929, Lilienfeld prepared a series of illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Loss of Breath. Poe’s short story tells of an actor who, in a fit of anger, loses his breath, though not his voice. Mr Lackobreath’s breath was stolen by Mr Windenough, a rival for the affections of the former’s wife. In the course of his adventures, Mr Lackobreath is assumed to be dead, thrown from a coach, run over, and dissected. He loses his ears and is attacked by hungry cats, and after being hanged on the gallows in the place of another, his body is taken down and interred in a public vault at the cemetery. Mr Lackobreath manages to free himself from the coffin – and meets his neighbour Mr Windenough, and claims his breath back. The tale is allegorical to the extreme, and possibly intended as a philosophical exposition on the body and its states. Here too, Lilienfeld rendered her illustrations in a reduced expressive style, adhering closely to the individual episodes of the story.

Hassidic subjects and the Legend of Baalschem

From the late 1920s, Rosy Lilienfeld became increasingly interested in Hassidic writings and tales, and prepared sketches on such messianic pretenders as the well-known figure of Shabbetai Zvi. Our collection includes individual sheets from this group of drawings. Her only published illustrations came from this group, appearing in 1935 in her book Bilder zu der Legende des Baalschem / Pictures to The Legend of Baalschem. This will be discussed in a dedicated blog article by Dennis Eiler, presently working in our collection as a student associate.

Looking to the future

Who was Rosy Lilienfeld? And what did she look like? Our collection has recently acquired an etching of a woman smoking. Is this the artist’s self-portrait?

Rosy Lilienfeld described herself as a painter, wood carver and graphic artist. As yet, only a small part of her printed works is known to have survived. She must have more or less given up painting in the early 1930s. In 1920s and 1930s, the art world was largely dominated by men. Women faced considerable obstacles in pursuing independent careers in art – even if individual women artists such as Ottilie W. Röderstein took considerable pains to support their female colleagues. It seems likely, then, that Lilienfeld’s book illustrations reflected her hopes of finding work, especially since after the National Socialist seizure of power she faced severe constraints on taking part in exhibitions or even buying canvases and oil paints. There was, though, a chance of her work appearing in cooperations with publishing houses abroad. Nonetheless, it was still several years before some of her illustrations were finally published in 1935 by the Vienna-based Löwitt Verlag.

Sascha Schwabacher and Margot Ries, the two art historians who wrote the Israelitisches Gemeindeblatt articles quoted above, followed and described Lilienfeld’s work and career. Just like Lilienfeld herself, they too were deported and murdered. This momentous and far-reaching fracture in art historiography is largely the reason why Rosy Lilienfeld is unknown today. As a result, working on Lilienfeld’s oeuvre is rather like trying to solve a puzzle where many pieces are unfortunately still missing. Hopefully, though, it will gradually be possible to complete the picture. Apart from Lilienfeld’s literary illustrations in our collection, I was also able to find nine of her drawings, illustrations of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, in the Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach (German Archive for Literature). Recently, the Jewish Museum Berlin has also been able to acquire some of Lilienfeld’s illustrations of the story of the pseudo-Messiah Shabbetai Zvi.

The search is continuing to locate and recover more of Rosy Lilienfeld’s scattered works. If you, dear reader, should come across any of her works – or even own any – I would be very pleased to hear from you!

Kommentare

Eine interessante Künstlerin. Wie schade dass Ihr Werk so wenig zugänglich ist. Gut, dass das Jüdische Museum daran arbeitet, sie wieder bekannt zu machen. Gibt es wohl mal eine Ausstellung zu Rosy Lilienfeld?

Ihr Kommentar